Academic Arzu Yılmaz: If Kurds go to the polls they will vote ‘No’

Arzu Yılmaz, of the American University of Kurdistan, saying the HDP’s Turkeyification project has collapsed, says, ‘If Kurds go to the polls, they’ll vote ‘No’, but only if they vote.’ Yılmaz said, ‘Turkeyification went up in smoke along with those who were burnt in the cellars in Cizre. If we are to speak of peace, we will only speak of this in terms of living side by side.’

Kemal Göktaş

In the run-up to the referendum, the polls show that the last-minute decisions of the undecided will be especially decisive. The pollsters are also said to be having great difficulty in measuring the Kurdish vote for a variety of reasons. The way things stack up is that the Kurdish problem, persistently ignored by the parties, will determine the referendum result. I spoke to Arzu Yılmaz, Head of the International Relations Department of the American University of Kurdistan in Duhok, who is known for her writings on the Kurdish problem and Middle Eastern politics, about the Kurdish problem, which has virtually become a forbidden topic since the ending of the solution process, and its effect on the referendum.

- In Turkey, the thesis on everybody’s lips is that the trench policy made losers of both the HDP and PKK. Has the Kurdish movement been defeated?

The PKK didn’t get the support of the people over its trench policy. There are a number of reasons for this. If we take the Arab Spring and events after 2011 as a benchmark, the HDP and PKK themselves accept that they failed in the policies they were pursuing on a Turkish scale. The HDP said in its Newroz message: ‘We stand in shame before our people for not having brought peace.’ There are two important things here. The first is the claim that the PKK fell into the AKP’s trap. The second is the inference that, if the people did not support this policy of the PKK, this automatically shows that their ties with Turkey are still strong. First, I don’t think the PKK fell into the AKP’s trap. The comments made by the KCK over that process quite clearly show that the PKK took this risk and was prepared to risk failure here in the interests of immediately consolidating its gains in Rojava.

- Their aim was for Turkey to expend its forces and energy in the South East so that they could protect their gains in Rojava?

Precisely. But, they were aware of the problems this would create. They saw these risks. They made a strategic choice cognisant of these risks. Instead of focusing on a solution here, they made a priority out of consolidating their gains in Rojava. I think that in a sense they sacrificed the Kurds in Turkey in political terms and in terms of mass support mindful of Turkey’s approach to Rojava.

- Was it not a kind of political suicide to sacrifice these gains made by the Kurdish movement, whose power had peaked in the 7 June elections, for Rojava?

It was not political suicide. It depends on how you look at it. In the end, what the PKK wanted was ultimately a struggle for power. The negotiations conducted in Turkey, that is the solution process, were (as they themselves clearly stated) based on a sharing of sovereignty between the Turks and the Kurds and this was planned as part of an endeavour for strategic cooperation on a Middle Eastern scale. As such, when seen from the PKK’s perspective, being the sole owner and participant of something small took priority over being part of something big. In the background to this was a hopelessness that had been learnt at the end of the experience in the 90’s. In view of considerations such as the sociological structure of the Kurds in Turkey, Turkey’s integration into the international system - for example, its being a NATO member, its land values and the importance it carries for the international system, it is harder for the PKK to establish its rule here than to establish a Kurdish rule in Syria. That is, establishing a rule in Rojava was perceived as being a something more easily and immediately realisable. So, despite in many respects the movement’s backbone, personnel, mass support and the power that dominates these being here, they poured all their energy into Rojava.

- Given that they have not entirely abandoned their goals in Turkey, what is going to happen in the time to come, then? What will their strategy be here?

The point of which sight must not be lost is that the PKK is the only Kurdish structure that is capable of organising militarily and politically in four countries where Kurds live in the region. So, it is perfectly understandable for an organisation resting on such a broad base and that is so broad and multilayered to make certain priorities in setting its strategies. Such zealous pronouncements from the solution process as, ‘Turkey will grow in the Middle East. Iran had better watch out from now on’ will be recalled. Those in Erdoğan’s entourage never tire of saying, ‘The Kurds betrayed us.’ The Kurds didn’t betray you. Your project was bad in the first place. Your project collapsed and the Kurds did not want to share their fate with you following the collapse of this project.

- This project collapsed with Erdoğan and Öcalan mutually declaring Rojava to be a red line. We saw this with the publication of the İmralı delegation’s notes from meetings with Öcalan. The HDP emerged as the fruit of Öcalan’s ‘Democratic Republic’ project. Does this not amount to developments in Syria blocking this project, too?

The solution process was not a Turkey project. It was a Middle East project. It was a project that aimed for strategic cooperation between Turks and Kurds in the Middle East.

- But this had to come about in Turkey.

Turkey had a projection which saw it acting in conjunction with the Kurds as it expanded in the Middle East and using the Kurds as a threshold to pass into the Middle East. What was the talk? ‘The Kurds won’t partition Turkey; Turkey will grow with the Kurds.’ The aim of the İmralı project was most certainly not to pacify the Kurdish problem in Turkey. Pacifying the Kurdish problem in Turkey was conceived of as a natural and indirect consequence of the strategic partnership to be entered into in the Middle East.

- Was this project conceived of from within Ottomanism?

Precisely. This is clearly coded in Öcalan’s 2013 Newroz message. For one thing, it was an anti-American, anti-imperialist and localist message that emphasised the cooperation of local forces and, in this context, foresaw a Muslim alliance. It doesn’t make reference to Lausanne. It prefers Çanakkale in its place.

- The HDP contested the election under a discourse of Turkeyification and a democratic left identity and gained 13% of the vote. It is said that the bonds of mutual affection nurtured during the Gezi protests and solution process contributed towards this success. Was this all a simulation?

None of it was a simulation. The HDP, after all, came into being after the proclamation of the İmralı process. In fact, the Kurds for the first time closed their own party and came to the HDP. This detail is very important. With their own hands, they closed the BDP and set up the HDP. The HDP is a political project that emerged as a product of the İmralı project at the point reached by the ideological transformation the PKK had been undergoing since the 2000’s. In keeping with the spirit of the İmralı process, it aimed to integrate the Kurds in Tukey into the system in Turkey. Were we to debate the matter in view of the 13% of the vote it gained, the crux of the debate would be whether it got that 13% of the vote for claiming that it would integrate Turkey’s Kurds into Turkey, or for its rhetoric, ‘We will not make you executive president.’ I am left wondering about this. Of the 13%, at most two or two and a half percent of that vote came from the left. The HDP got most of its votes from Kurds on 7 June. We saw how the Kurdish lands consolidated in political terms behind the HDP. This gives us a very important message: In the final analysis, the HDP’s discourse of integrating the Kurds into Turkey did not find uptake in the West of Turkey but among Kurds themselves. This is very conducive to understanding the situation in the aftermath of the trench policy or in the run-up to the referendum. Hence, 7 June must be interpreted with great care. The energy that 7 June essentially released was the support it gave the project of integrating the Kurds into Turkey. The expectation of Kurds was not for Selahattin Demirtaş and the HDP to integrate with Cihangir and the Turkish left and Istanbul or to carry the latter’s thoughts to Ankara, but to carry the Kurds to Ankara. The HDP ultimately opted through the preferences it made and through campaigning in the election under the slogan it had adopted of ‘We will not make you executive president’ to carry the demands of Istanbul and Cihangir or the Turkish left to Ankara. In spite of this, the Kurds thought, ‘Even so, for as long as we Kurds have the HDP in parliament, a footing will be created from which our rights can be recognised or our sovereignty rights shared within the context of autonomy.’ However, Sırrı Süreyya Önder, with the official results yet to be announced and the party’s general chair yet to make a press statement, came out and said, ‘We will not betray the floating vote.’ How large was the floating vote? And so, the upshot among Kurds was the idea: ‘You are entering parliament on 7 June with a vote that gives you 80 MPs thanks to us and with our kids rotting and dying in jail, with our vote, but your policies do not meet our expectations. How about giving priority to not betraying the 11% floating vote over not betraying the 2% floating vote?’

- Were these really mutually exlusive things?

This was not a matter of exclusion, but one of priority. The Kurds believed that peace would come with Tayyip Erdoğan. The Kurds had never been able to come into close proximity to the state, but they did not see Tayyip Erdoğan as the state, but in the end Erdoğan, too, fused into the state.

- That’s how they saw him in the 1 November process, though

The business basically changed with Kobani, that is, in October 2014, but on 1 November the HDP’s share of the vote fell, because, just as in the referendum now, post-7 June politics did not speak to the Kurds. The Kurds said, ‘We sent you there to constitute a force for solution and what are you doing?’

- It was also said that the HDP’s 13% caused consternation in Qandil. There was a comment by Demirtaş. To the effect that ‘Politics is available for solving this affair.’ I mean, in a sense, this was the message to Qandil. Was there this kind of competition between them?

There has always been this tension in the PKK. This is not something peculiar to the HDP. This tension has always existed as long back as the 90’s. People like Leyla Zana, Orhan Doğan, the DEP, DEHAP and DTP... There is a dimension of this tension that accounts for the 7 June and 1 November process, but this is not the full extent of it.

- Could the 13% have exasperated this?

What Qandil said was: ‘You will use the 13% in Rojava politics which is our priority, so as to influence Turkey’s Rojava policy. Our priority in strategic terms in Rojava.’ Politics may have come to the fore in Turkey, but a hugely destructive war was going on in Rojava. Let us not forget the policy the AKP followed in Kobani in 2014. Even though recognitiion of the Kurdish entity in Syria had been agreed on in principle in a very serious manner in the peace process, the AKP never kept its word. Anyhow, if you look from within the context of Turkey, the AKP kept on closing off the political arena a little more each day from that day.

- You are saying that the two per cent vote imposed its will on the eleven per cent?

Yes. This made the Kurdish masses uneasy. Secondly, in the end there may not have been war in Turkey but the PKK was in a war. Ignoring the policies followed by Turkey in this war and making space for politics on a purely Turkish scale did not fit in with the PKK’s logic. If we look from within Turkey, we can say there was no war here and such a high degree of representation was achieved in politics, but that story is over. Today, going forward, the international system does not regard the Kurdish problem either solely on a Turkish scale or solely on an Iraqi scale, nor do Kurdish politicians act on this basis. They cannot in fact do so. The nature of the affair has now changed. The nature of the Kurdish problem has changed. To interpret the HDP’s story solely in terms of political events occurring in Turkey does not provide us with adequate information about what really went going on. We also have to include in the analysis what Turkey was doing in Rojava at that time. The affair cannot be explained away with the simplification that Qandil did not want the politicians in the plains and got jealous.

- There is tension, though. What is the reason for this tension?

This has always been going on. In the final analysis, the PKK is an armed organisation. It also has a hierarchic system that is part and parcel of such armed organisations. But, in spite of this, the PKK operates a decision-taking mechanism through the KCK formation in which its military policies, civil society and other such things are combined. For example, the PKK declared a ceasefire prior to 1 November. The press missed this. Nobody spoke about this. This, for instance, is an example of politicians making their voice heard against the military wing within the KCK.

- Is it not a ceasefire that became ineffective with the 10 October station massacre?

Precisely. Nobody saw this. Had the HDP managed through its election strategy and its post-election strategy to retain the support of the body that essentially took it there, it could have been a far stronger cog in the decision-taking mechanism within the Kurdish political movement. But, the HDP mortgaged itself within this structure for the sake of that two and a half per cent floating vote. And this was detrimental to the HDP’s support among the Kurdish masses. A world in which peace was made in Turkey and war waged in Syria was not on for the Kurds, and not just from the PKK’s strategic perspective. This assumed a character of a very wide-ranging nature. And this wide-ranging character made the solution more difficult.

- The HDP is waging a ‘No’ campaign over the referendum. Do you think this will be unsuccessful?

The referendum is not a big issue in the region. I live there. There is no big issue over the referendum in Diyarbakır, Şırnak, Cizre or Nusaybin; in the region. They say, ‘What does it matter if ‘Yes’ prevails or ‘No’ prevails.’ People have vital concerns, they are concerned with normalising daily life. Extraordinary conditions of war prevail there.

- Do they not think things will get harsher if an executive presidency comes in?

This kind of thing is doing the rounds like a rumour, but, you see, there is no clear message as to what the presidential project holds for the Kurds. So, why should the Kurds be interested in a referendum having to do with the presidency?

- But it affects other things. The alliance with the MHP promises to give permanence to this situation. Is this not an issue that has a direct impact on people’s daily existences, lives and freedoms?

The referendum makes no promises to Kurds as to a solution to the Kurdish problem through the presidential system. Second, regardless of whether ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ prevails in the referendum, Erdoğan will continue to be this country’s president, and Yıldırım will be Prime-Minister. Kılıçdaroğlu has also said this. What is the most that can happen? What currently applies can happen. What will happen if ‘No’ prevails in the referendum? Will there be a change of power in Turkey?

- Is the matter of limiting power not important?

There is no such expectation because the Kurds have actually long since given up complaining about Erdoğan. The main reason for Kurds’ lack of hope about Turkey is the absence of an opposition.

Scores have been settled with Erdoğan: ‘We trusted this man but he, too, fused into the state’ is how this is expressed in popular language. ‘Erdoğan fused into the state and was finished.’

- Will this thought not boost the ‘No’ vote?

I don’t know. But, it doesn’t look like the Kurds will go to the polls just to say ‘No’ to Erdoğan. There needs to be a projection as to what follows ‘No’. What does the HDP say? A shared homeland and a democratic republic. People’s homes and lives have been brought down over their heads. They don’t even care enough to flee to the west of Turkey, can you conceive of that? For example, in the nineties, the west of Turkey was an alternative even if just to flee to. Today, the west of Turkey is not even an alternative for Kurds to flee to. At the end of the day, from what I’ve seen, if Kurds go to the polls, they’ll vote ‘No’, but only if they vote.

- OK, where will Turkey’s Kurdish problem go?

My opinion is that the shortest reply within all this cacophony to the question of what’s going to happen is, in my view, Turkey’s capacity to create a solution to the Kurdish problem based on its own internal dynamics has now vanished. From now on, the Turkeyification project is a dead duck. It doesn’t matter if you blame the trench policy or if you blame the AKP. But, combined with the destruction that we have experienced over the past two or three years, the Turkeyification project went up in smoke along with those who were burnt in the cellars in Cizre. Going forward, we will speak with reference to Turkey’s and Turkey’s Kurds’ problems and this process of conflict, not of unification, but at most of formulas for living side by side. If we are to speak of peace, we will speak of this in terms of living side by side or, even worse, of how we are to separate. This has a very direct relation, not just to the AKP or the HDP’s policies, but to overall developments in the Middle East. Today, neither the international system, nor the Kurds themselves, nor events in Kurdish politics are on a scale that permit us to think solely within Turkey’s, solely within Syria’s or solely within Iraq’s borders. We also know from history that, once the nature of certain things changes, it is then impossible to turn them back.

- In that case, we can ask where the Middle East’s Kurdish problem will go.

We can say that the policy the AKP is following today with regard to the PYD is irrational. But, it you look at the heart of the matter, the AKP is right in one respect. The independence of Iraqi Kurdistan will become a reality, if not today then tomorrow. A Kurdish administration in Rojava will have effects on Kurds in Turkey and Iran. This is a correct reading, but the strategy they have developed in the light of this reading is wrong. They cannot manage it like this.

- Russia and the USA have caused great disappointment for Turkey recently. Russia has gained a presence in Afrin through bases or branches. Is this a sign of Turkey being isolated there and the Euphrates Shield operation being brought to an end?

In 2011 Obama said, ‘I’m pulling out. I have no business in the Middle East anymore.’ Erdoğan set out to run the US’s Grand Middle East Project, in which it had envisaged a presence for itself and a presence for Erdoğan, to the exclusion of the USA and with an Islamist interpretation. As the Arab spring erupted around this, tension with the US became a little more strained with each day that passed. At the end of the day, you cannot run foreign policy like a sharp dealing small trader. This business doesn’t work by selling for five quid something you bought for three when the chance presents itself. Foreign policy cannot be run with your personal ambitions in mind. You have to take stock of the needs and balances of the international system. Once the ground you are standing on slips, you will have trouble getting back on your feet once more. This is the position Turkey is in just now.

- Barzani is making preparations for an independent state. Can he succeed in this? Domestically there are plenty of problems. Will he do this with Turkey’s support?

Not with Turkey’s support. The prospect of Iraqi Kurdistan becoming an independent state is a prospect that has been on the table since 1991. But the Kurds last attained the capacity to realise this prospect when the USA occupied Iraq in 2003. We now learn from politicians’ explanations that at that time the USA told the Kurds, ‘We will make a constitution and recognise you as a federal state’- because, in the federal state structure, Baghdad had no hierarchic authority over Erbil. The system itself did not create hierarchical superiority among the federal states. It did not stop here and Hoshyar Zebari was the Foreign Minister of Iraq of which Talabani was President. So, it said to the Kurds, ‘Today is not independence day, but we are creating an environment that will provide you with the opportunity for Kurds to establish rule in Kurdistan.’ When Barzani had attained the capacity to control the disputed area as happened in 2014, he thought this was now the right time to declare independence. After all, there remained no country called Iraq after 2005. We pretend there is, because the Kurds are still within that whole. The USA also tells us that Iraq exists. It addresses Baghdad. When it sends arms, it does so through Baghdad, and so on. But there is no state called Iraq. Today, even if ISIL is removed from Mosul, in a place where there is no state, today ISIL and tomorrow another acronym will come. There was Al-Qaeda and ISIL came. It will go, something else will come. And the Kurds say, ‘We said “OK” in 2005, but with current developments the absence of a state in Iraq has come to threaten our lives. It is supposed to give us a seventeen per cent share under the constitution, but is not doing so. It cannot provide us with security. In economic terms, it is not giving the share of the budget it has pledged to under the constitution. We are trying to establish an order in which we assure our own perpetuity. It does not permit us to enter into economic engagements to this end. We’re through.’ Most recently, peshmerga participation was critical to the Mosul operation. From what I have been able to learn, they reached political agreement over Mosul with Barzani in Baghdad without the need for a referendum over borders. Baghdad has no objection to Iraqi Kurdistan’s independence. Why is this independence a problem? If Iraqi Kurdistan’s independence is to be delayed, why so? It is because the effect of this independence on Syria or Turkey cannot be gauged.

- What is feared?

Uncertainty is feared. There is stability neither in Turkey nor in Syria. Developments could fly entirely out of control at any moment. It is unknown where such a proclamation would take things.

- Would Iran get mixed up in this?

Iran has got mixed up a lot since 2004 in any case.

- I mean, would there be an intervention going as far as actual combat?

There is a low probability of this because it is clear that following ISIL the international system is going to reposition itself with regard to Iran. At least, it is clear that this is what Trump will try to do. We can presume that Iran will revert to minding its own affairs in this environment. Iraqi Kurdistan’s independence is simply a matter of time now. The uncertainty as to whether this will be today or tomorrow arises from the inability to foresee the effect of an independent Kurdistan on other countries. The inability to foresee this in the environment of chaos and the environment of uncertainty is a major factor. There is a very serious pressure that this exerts on domestic politics in Kurdistan, in a tangible way. On the one hand, we know that historically and ideologically the KDP and Barzani have never had designs, claims or projects as far as the Kurds in other countries are concerned. It needs to have a presence in Syria and Turkey today, however unwillingly, but it is also clearly not getting ready for anything.

- Does Turkey aim to increase Barzani’s influence over the Kurds in Turkey?

The capacity for the people who are to administer Kurdistan to influence Kurds living in other countries will be considerable. But, as far as I have seen, neither Barazan nor any politician in Iraqi Kurdistan in general has done any groundwork with this in mind. There is this kind of reality that life has imposed and speedy, dynamic developments within politics have imposed. They are now trying to come to terms with this, but they do not know how to do so. Were we to list the obstacles in the way of independence, one of the most important parameters is what will happen in Diyarbakır or Kobani. Baghdad has long been prepared for this. They say in Baghdad, in parliament, ‘Why are we giving these people 17% - what use is it to us?’ Nobody has any expectations from Iraqi Kurdistan any more. It is all a matter of the USA not yet knowing what to replace a partitioned Iraq with.

- Can the conflict that has erupted between the PKK and the peshmerga in Sinjar spread? There is talk of Turkey conducting an operation against Qandil. Will this lead to renewed KDP-PKK conflict?

It will not be like in the 90’s.

- Can conflict take place?

There was conflict and meetings were held in Erbil. No agreement could be brokered. Rifles are trained on one another and they wait in deadlock. Various formulas were spoken of. No agreement could be brokered over any of these formulas. At this point, it is necessary to say that we frequently hear the comment, ‘The Kurds are undergoing birth as a new actor in the Middle East.’ Yes, this is certainly true, but the performance of Kurdish political actors over the past five years shows that they are not well prepared for this birth. They are handicapped in this. Öcalan is in jail, Talabani is ill and Barzani’s capacity does not permit him to manage this potential and energy. The Kurds obtained an exceptional opportunity in a very important period of history, but were found wanting as to their readiness in leadership terms for this opportunity. I say this because you asked about Sinjar. Due to this lack of leadership mission the Kurds have been unable to develop the capacity to solve their own problems. They have done nothing worthwhile. They have been unable to convene a national conference. They have done nothing in practice to develop cooperation mechanisms among themselves. It remains to be seen whether they will display the ability to transform their military successes into a political success.

- Is there no chance of them losing at the table thanks in particular to having entered such close relations with the imperialists?

There is a risk. They also know this. But, on the other hand there is the fact that states are collapsing one by one and the old alliances have run out of steam and there is no second force that they have cooperated with as much as with the Kurds. At the end of the day, we are in a period in which states are unable to perform their functions and armies are left without a job to do. There is no such thing as the Iraqi army. Virtually all armies in the Middle East are at war with their own people. So, in the Middle East, where states don’t function, armies have no job to do and the connection between states and life has been broken, it is not rational for an organisation to be dispensed with that has developed a national awareness, has managed to maintain a military organisation at a level at which one can speak of becoming an army and has attained the capacity to cooperate with international actors.

- Is there no prospect of the PKK losing the support of Kurds in Turkey following its prioritisation of Rojava? Is such a rupture possible in the medium and long term?

A rupture is unlikely. But, if an alternative is to arise, this will also arise from within the PKK, because it has had the opportunity to infiltrate various strata of society for such a long time that it is now virtually impossible to separate the PKK from the Kurdish reality. So, I do not imagine there will be anything like a rupture from the PKK, but the PKK needs to reorganise itself internally. The PKK has projects to cease being a terrorist organisation and find inclusion as a political actor within the Middle East system. The PYD is one such project, anyway. The USA calls the PKK a terrorist organisation, but, on the other hand, says the PYD is not. This was ignored at a time when the fight against ISIL was a priority, but, with the fight against ISIL now drawing to an end, it is telling it to gradually withdraw to Qandil from Sinjar. On the road from the battlefield to the political table, this is also the way to present the PYD as being a legitimate and legal actor separate from the PKK. The PKK has no objection to this, actually. Just like in the peace process in Turkey, the only thing it says is, ‘Don’t do this to our exclusion – do it together with us.’ In the final analysis, the PKK people themselves do not dismiss this fact. When the impossibility of an organisation that has grown this much carrying on with Qandil as its headquarters and its leader in prison and the urgent need it feels for an immediate success story are taken in conjunction, the PKK has no objection when it comes to reorganisation. But, its objection is: ‘Do not do this to our exclusion. We want to be part of this project, too.’ The people in Qandil are concentrating on obtaining a result that has the capacity to bring off a revolution. They, too, are aware that it is impossible for either problems, or responsibilities, or indeed the organisation, to be handled in this way.

- What will be the HDP’s political future?

The Turkeyification project has finished. What was the story? The HDP and DBP were founded at the same time. The HDP would address Turkeyification, while the DBP would address the region. In the end, the HDP was faced with the necessity from 2013 onward of conducting the presidential election and then general elections etc. as both the one being Kurdish and the one being Turkeyish rolled together. But it was unable to achieve this balance. In fact, Turkeyification and the democratic republic theses opened a path for the Kurdish political movement to continue on its way following the trauma it experienced in the 90’s. The notion of a democratic republic was actually a path that opened up enabling it to continue on its way following the disappointment experienced in the 90’s. Unfortunately, it could not turn this path into a main road. The place we have reached, unfortunately, is a place in which the will to cohabit has not strengthened, but has weakened or virtually disappeared. The HDP in my view lacks the wherewithal to continue from this place it has reached. At the very least, life is not flowing in the direction of Turkeyification. The HDP is the story of another thing. That story has finished. Now a new story is being written. We don’t know yet. We had our story: ‘The Kurdish problem is Turkey’s internal problem. On becoming a democratic country and with everyone’s rights being recognised, everything will be great. We, too, will be able to go to Istanbul and eat our fish accompanied by raki. They will also experience nostalgia in the remote corners of the country and we will all call ourselves brothers.’ This story has finished. We will not have a world like this. At least, the Kurds are not buying this story. They don’t know what kind of story is starting, either.

- Is it correct to speak of the Kurds collectively? It is frequently said that the middle classes have different inclinations.

There are always different groups that have the potential to exert an influence within society. But there needs to be an atmosphere to feed this. There has to be an atmosphere from which it can get oxygen. The class that was harmed the most by this destruction was the middle class.

- But, both white-collar workers and people involved in commerce are integrated into Turkish capitalism. Opinion leaders also exert an influence over society.

That power of theirs to exert an influence is impossible with the oxygen supplied to them in the overall political atmosphere. That oxygen is lacking. That air has now become poisoned. Those people are not in a position to come out and make any comments. Their arms bled and are broken, too.

- These quarters appear to attribute responsibility for what has happened mainly to Qandil.

It no longer maters whose fault it was. There’s a corpse out there.

- Does it not matter who the culprit is?

The blame for this will be attached but, in my view, both parties bear responsibility for this murder. What now concerns me, rather than the question, ‘Who committed the crime,’ is for it to be asked, ‘How are we to dispose of this body?’ That’s the issue.

En Çok Okunan Haberler

-

CHP'ye yeni transferler: Rozeti Özel takacak

CHP'ye yeni transferler: Rozeti Özel takacak

-

Tartışmalar sonrası istifa etti! Yeni CEO eşi oldu

Tartışmalar sonrası istifa etti! Yeni CEO eşi oldu

-

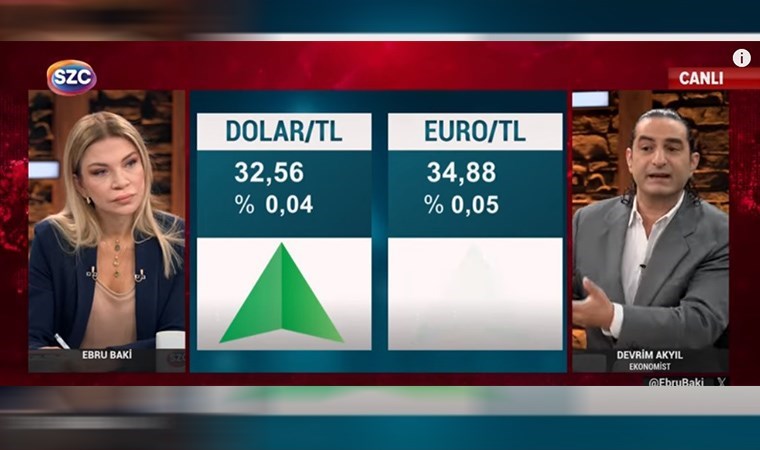

Canlı yayında 'dolar' tartışması: Tansiyon yükseldi

Canlı yayında 'dolar' tartışması: Tansiyon yükseldi

-

Yandaş ‘gazeteci’den tepki çeken çıkış

Yandaş ‘gazeteci’den tepki çeken çıkış

-

'Müzakere edilmez!'

'Müzakere edilmez!'

-

Mevduat hesaplarında yeni dönem

Mevduat hesaplarında yeni dönem

-

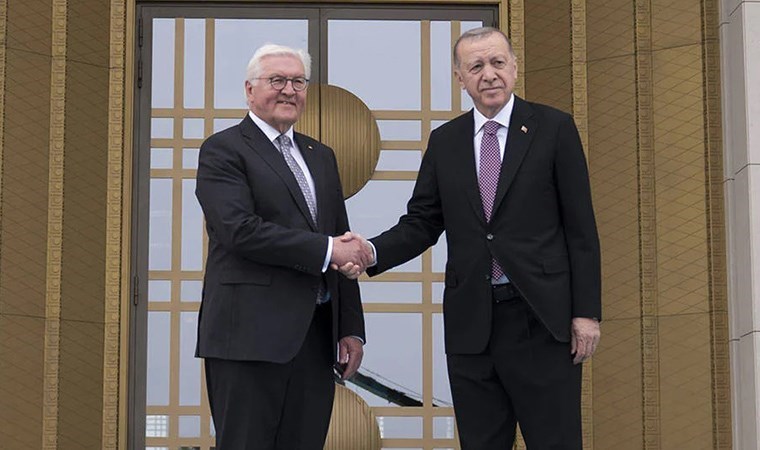

Erdoğan ve Steinmeier'ın diyaloğu gündem oldu

Erdoğan ve Steinmeier'ın diyaloğu gündem oldu

-

Mersin’de hasat erken başladı: Kilosu 45 TL

Mersin’de hasat erken başladı: Kilosu 45 TL

-

'Şu an Cumhur İttifakı'nda mısınız' sorusuna yanıt

'Şu an Cumhur İttifakı'nda mısınız' sorusuna yanıt

-

Mehmet Ali Yılmaz evinde ölü bulundu!

Mehmet Ali Yılmaz evinde ölü bulundu!